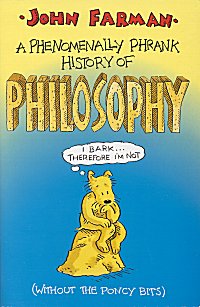

Review: A Phenomenally Phrank History of Philosophy

- Title

- A Phenomenally Phrank History of Philosophy

- Author

- John Farman

- Publisher

- Macmillan, London, 1996

- ISBN

- 0-330-34555-9

Review Copyright © 1999 Garret Wilson — January 3, 1999, 1:30pm

I have always been an advocate of books that explain things in simple terms. Some introductory works have been reported to make things simple without "talking down" to the reader; what is the "talking down?" If I don’t know the information to begin with, I figure I shouldn’t take offense at simplification. John Farman certainly "simplifies" philosophy in his phenomenally short A Phenomenally Phrank History of Philosophy. But whether he makes it easer to learn is another question.

The question I haven’t figured out just yet is whether Farman is talking down to me or just talking stupid. It doesn’t start out so bad: "The grumpy Egyptians had been obsessed by death, believing their souls would eventually descend to the fiery underground to be met and judged by a chap called Osiris who grilled them (in more ways than one) about what they’d been up to on earth" (3). You’ll soon find out that this arbitrary sentence is indicative of most sentences in the book: colloquial ("they’d been up to on earth"), British ("chap"), full of puns ("grilled them"), and condescending ("grumpy Egyptians"). I’m all for humor, memory tricks, or whatever is needed to learn something. After a few chapters of almost every sentence being both stupid-funny and condescending (to someone, usually the philosopher involved), it almost gets tiresome.

Part of the problem with this book is that it is so short. The 139 pages (including the index) will be one of the shortest sets of 139 pages you’ve ever read. The other problem is that it covers so much. From Thales of Miletus (4) to Jacques Derrida (129) Farman covers the major philosophers and you’ve heard about and surely a dozen whose names won’t sound familiar to the average person. Since he covers some philosophers other more "serious" books only mention, you can calculate that you’ll only find a paragraph or two on most philosophers.

This sparse coverage, while entertaining, doesn’t really give enough information to give anything to the reader by which he/she can remember the person in question, or even to understand the issues involved. For example, half of his Hegel description reads:

The Greek philosophers like Socrates, Plato, and Co. were mostly interested in man, and were not that bothered with the universe, provided it didn’t get in the way of said man and his mates [Britishism, again]. Through studying this long suffering man, they came up with their concepts (often hilarious) of the universe. But Hegel maintained that whatever conclusions they came to had to be right for the amount of knowledge they had and the point in history in which they lived (76)

Hegel maintained that history is lurching slowly, in fits and starts, backwards and forwards, towards a perfect state, in which every member of the society blends perfectly with everyone else, and his will (or what he wants to think or do) is the same as everyone else’s — a kinda world spirit. Seriously, if I believed that, I’d sleep much better at night" (77).

Admittedly, these few paragraphs (ignoring the sarcasm) do quite a good job of summing up some of what Hegel believed. But when there are so many philosophers mentioned and only a couple of paragraphs are given to most of them, what some obscure philosopher on the last page might be forgotten as one reads about a famous philosopher on the current page, and the next page may cause the reader to mix up all the ideas. In short, the book has as much sarcasm-filler as it does information about philosophers — and it has too much information about philosophers for a book it’s size.

Then again, maybe I’m taking the book more seriously than it was meant to be taken. This is, after all, a Macmillan Children’s book, and the back cover claims that, after writing the book, Farman "can now hold his own (and often does) quite convincingly for seconds at a time, in any deep and meaningful conversation about life, the universe, and all that." So, taking the book as a jolly-fun dash through philosophical history to make one laugh and maybe even think once in a while, let’s turn to the content itself.

Haraclitus (6) gets an entire paragraph, and Farman ridicules him for "being big on opposites" and saying you can't know what it's like to be warm if you've never been cold, etc. Farman asks, "Does that mean that unless you’d been tall, you’d never know what it was like to be short?" In a more abstract way, it makes a lot of sense to me. You might not have to be tall to know that you’re short, but isn't it true that there have to be tall people for there to be short people? Did the Pygmies know they were short before taller people showed up?

Farman explain’s Zeno’s (23) idea that an arrow takes up the same amount of space in flight at any time so at any time during the flight it must be at rest. "Try telling that to a dead cowboy," quips Farman, but ignores the amazing relation of this idea to modern ideas of relativity. Einstein showed that while an arrow is in flight, it actually takes up slightly less space than if it were at rest. Zeno’s paradox has therefore been solved. But Farman doesn’t mention this. Maybe he forgot this paragraph in his Suspiciously Simple History of Science and Invention (which he really published).

Farman portrays Berkely and Hume (54) as preaching that one is not able to know for sure if anything exists (although it was not immediately clear to me that this was Descartes’ (45) idea). Amazingly, this sounds a lot like what I wrote in an essay at the University of Tulsa in 1995 entitle, "Consciousness, the Observer, and Whatever Else I Think I Think of," written long before I had read anything of Descartes, Berkeley, or Hume (except for some of Hume’s morality stuff). This should be no surprise, though, since I’ve been steeped in scientific readings which are ultimately based on these philosophers’ ideas.

Those strange figures in The Worldly Philosophers actually have some relevance: According to Farman, Comte (77), who believed that human society goes through clear-cut stages, was secretary of "the famous writer" Saint-Simon. I’m guessing that this is the same Count Henri de Rouvroy de Saint Simon portrayed in The Worldly Philosophers (117). Furthermore, Farman explains that Darwin (yes, he covers about everyone who could remotely be called a philosopher) got some ideas on natural selection from an essay by Thomas Malthus (91), whose works is also related to economics as explained by The Worldly Philosophers (77).

Farman's snide remarks many times ironically lend credibility to the idea he is ridiculing. "[Marx, from Hegel] gained... the belief that change was simply a road to better things... Even a society that appeared to be OK at the time, he said, would inevitably give way to another that was better (our latest government? Please!)" (83). Would not Farman agree with Marx/Hegel, though, if he were to compare his "latest government" with that of, say, 300 years ago?

Towards the end of the book, Farman begins to cover the later philosophers less and less comprehensively (although this is hard to imagine). Farman himself admits as much, although he attributes this to the later philosophers being "smart-arse[s]" and self-indulgently trying to "shoot [the other person’s work] down in flames." "...as I neared the end of this mighty [?] work, I was spending more time in the dictionary defining each word than I was trying to interpret what they all meant when strung together" (133). This means, if you remember anything from the beginning of the work, by the time you get to the end it all seems less and less relevant, interesting, or coherent.

The book is not hard to understand, though many Britishisms, such as "pants" used for "underwear" (68), may be unfamiliar to some American readers. (No, underwear does not directly relate to any of the philosophers’ ideas, they were simply part of Farman’s sarcastic remarks.) The book is not unenjoyable, either. It doesn’t even take a lot of time. I’m just trying to figure out who should read it. It covers way too much ground in too little time for a beginner, it’s short descriptions leaving nothing much to remember and even less from which to derive some sort of coherent overview. (Hegel, if he would have remembered anything from it, might not have found a Spirit in Phenomenally Phrank History of Philosophy.) And philosophy experts will find nothing of interest in the book, unless they enjoy a lot (and I mean a lot) of stupid-pun-ful humor (or should I say, "humour.") Phrankly, I can only recommend the book to those who have read some about philosophy and need a humorous break and want to get a quick summary of what they’ve learned so far, deriving a few pointers on where they might want to look next.

Copyright © 1999 Garret Wilson