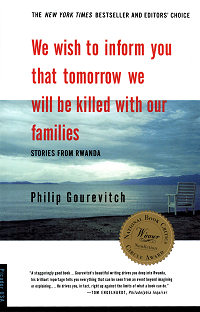

Review: We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families

- Title

- We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families: Stories from Rwanda

- Author

- Philip Gourevitch

- Publisher

- New York: Picador, 1998

- ISBN

- 0-312-24335-9

Review Copyright © 2005 Garret Wilson — 25 January 2005 10:30pm

Today the United Nations, in its first-ever special commemorative session, marked the 60th anniversary of the ending of the genocide under the Nazi regime during World War II (BBC). Secretary-General Kofi Annan noted that it is easy to "say, 'never again'. But action is much harder. Since the Holocaust the world has, to its shame, failed more than once to prevent or halt genocide – for instance in Cambodia, in Rwanda, and in the former Yugoslavia."

Kofi Annan should well know, as Philip Gourevitch points out in his documentary-like book on the Rwandan genocide, We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families: Stories from Rwanda. Kofi Annan in 1994 was the chief of UN peacekeeping when that department received an urgent message from the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda, indicating that the ruling ethnic Hutus were registering ethnic Tutsis, apparently in preparation for their extermination. Annan's deputy, Iqbal Riza, rejected the included proposal for action (105). Throughout the genocide that soon followed, the United Nations, the United States, France, and most other countries turned a blind eye to the slaughter that took place at a rate faster than during the Nazi killing of Jews during World War II.

Three years later, then Secretary of State Madeleine Albright admitted that "We, the international community, should have been more active in the early stages of the atrocities in Rwanda in 1994, and called them what they were—genocide" (350). (To her credit, Albright seemed to have received sufficient practice in apologizing for United States actions.) As Annan pointed out today, the Genocide Convention of 1948 was created to prevent the horrors of World War II from being repeated. But as the killing raged in Rwanda, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights was using the term "possible genocide" to describe events, apparently afraid that calling a spade a spade would require action under the Convention. The United States didn't want even the appearance of responsibility, and the Clinton administration actually forbade unqualified use of the term, "genocide" (152). State Department spokesperson Christine Shelley explained the touchy subject in June 1994 in response to a question at a news briefing:

Q: So you say genocide happens when certain acts happen, and you say that those acts have happened in Rwanda. So why can't you say that genocide has happened?

MS. SHELLEY: Because, Alan, there is a reason for the selection of words that we have made, and I have—perhaps I have—I'm not a lawyer. I don't approach this from the international legal and scholarly point of view. We try, best as we can, to accurately reflect a description in particularly addressing that issue. It's—the issue is out there. People have obviously been looking at it (153).

Fast forward exactly 10 years to Sudan, where militias are (to this day) targeting black African civilians in the region of Darfur. In the summer of 2004, various groups called for the Bush administration to label the killings as "genocide." Reminiscent of Rwanda, the administration first refused to use the word, even after the U.S. House of Representatives unanimously passed a resolution in July explicitly invoking the term "genocide" in describing the Sudan events. President Bush and Secretary of State Colin Powell finally acquiesced and uttered the word months later but, in a move now common in the Bush administration, Powell explained that a determination of genocide would raise no obligations on the part of the United States to change its policy towards the Sudan. (Scott Straus, "Darfur and the Genocide Debate," Foreign Affairs, January-February 2005 (123-133).) (The Genocide Convention of 1948, after all, is one of the Geneva Conventions, which haven't found much enthusiasm with President Bush and those he chooses to lead the United States in its "War on Terrorism.") Perhaps Madeleine Albright can return a few years from now and deliver more apologies.

Philip Gourevitch, a reporter for the New Yorker, traveled to Rwanda shortly after the killings stopped and collected first-hand accounts of those who actually lived through the genocide—on both sides of the machete. The book goes beyond good reporting to provide a moving, informative primer of a situation created by years of colonial promotion of racial divisions between Hutus and Tutsis, a population accustomed to being told what to do, and a political power structure intent on exclusive control. The Huto Power government managed to persuade common citizens to kill over 800,000 of their Tutsi friends and neighbors:

With the encouragement of such messages and of leaders at every level of society, the slaughter of Tutsis and the assassination of Hutu oppositionists spread from region to region. Following the militias' example, Hutus young and old rose to the task. Neighbors hacked neighbors to death in their homes, and colleagues hacked colleagues to death in their workplaces. Doctors killed their patients, and schoolteachers killed their pupils. Within days, the Tutsi populations of many villages were all but eliminated, and in Kigali prisoners were released in work gangs to collect the corpses that lined the roadsides. Throughout Rwanda, mass rape and looting accompanied the slaughter. Drunken militia bands, fortified with assorted drugs from ransacked pharmacies, were bused from massacre to massacre. Radio announcers reminded listeners not to take pity on women and children (115).

Apparently to mark the 10th anniversary of the Rwandan genocide, a movie named "Hotel Rwanda" has just been released which follows the same Paul Rusesabagina recounted by Gourevitch as he works to save the lives of Rwandans in the hotel he was managing. Although not explicitly mentioned, it appears from the book that many of those saved in Rusesabagina's hotel were elite Tutsis, and/or those who could afford to bribe someone to help get them to the hotel. While Rusesabagina's work is to be commended, the vast majority of Tutsis had no hope of being helped by any hotel or even church. The title of Gourevitch's book, in fact, recalls up to two thousand refugees in a large church in Mugonero who sent a letter to their pastor asking to be saved from the slaughter:

Our dear leader, Pastor Elizaphan Ntakirutimana,

…We wish to inform you that we have heard that tomorrow we will be killed with our families. We therefore request you to intervene on our behalf and talk with the Mayor. We believe that, with the help of God who entrusted you the leadership of this flock, which is going to be destroyed, your intervention will be highly appreciated, the same way as the Jews were saved by Esther (42).

Instead, most of those holed up in the church met the fate of many of the Jews of Auschwitz 50 years earlier, except that in this case machetes were used instead of gas chambers. Those interviewed by Gourevitch recall Pastor Ntakirutimana instructing Tutsis to gather at the church and later accompanying militiamen and members of the Presidential Guard (27). Later in the book Gourevitch even manages to inverview Pastor Ntakirutimana at his home in Texas (40).

Gourevitch tells the facts and lets the people themselves tell the facts again. Then Gourevitch tells his opinions, and he has plenty of them: about the carelessness and naivety of aid workers; about the apathy of the Americans; and above all about the nigh complicity of the French from digging in their heals to providing weapons to Hutu Power members. His quote of President Mitterrand is abhorrent, if scarcely believable:

In 1994, during the height of the extermination campaign in Rwanda, as Paris airlifted arms to Mobutu's intermediaries in eastern Zaire for direct transfer across the border to the génocidaires, France's President Francois Mitterrand said—as the newspaper Le Figaro later reported it—"In such countries, genocide is not too important." (324-325).

Gourevitch notes that the genocide was not a hidden affair, and should have been obvious from early on:

[T]he government was importing machetes from China in numbers that far exceeded the demand for agricultural use; and many of these weapons were being handed around free to people with no known military function—idle young men in zany interahamwe getups, housewives, office workers—at a time when Rwanda was officially at peace for the first time in three years (104).

Gourevitch does not spare the aid workers attending to the Hutu refugees who fled the country as the Rwandan genocide came to a close:

[W]hat made the camps almost unbearable to visit was the spectacle of hundreds of international humanitarians being openly exploited as caterers to what was probably the single largest society of fugitive criminals against humanity ever assembled (267).

But above all Gourevitch brings us the personal side of the killings with interviews and descriptions of those affected by the tragedy. Through a book of journalism, Gourevitch asks us to ask ourselves how many "never agains" will be enough. These stories from Rwanda are diverse, yet are typified by the letter informing the pastor that "tomorrow we will be killed with our families," and by the fax received and rejected by Kofi Annan's department in 1994: this was a tragedy that could have been stopped, had those who run the world determined that it was in their interest to do so. As Annan pointed out today, actions are much harder that words. As today's leaders start their slow-motion semantic dance around the events in Darfur, perhaps another look at We Wish to Inform You could give direction to their steps. The question raised by one of Gourevitch's central characters, Odette Nyiramilimo, remains relevant: "Do the people in America really want to read this" (238)?

Copyright © 2005 Garret Wilson