Review: Woody Guthrie: A Life

- Title

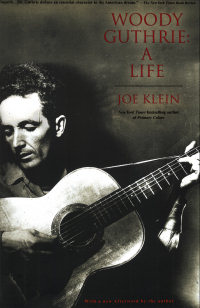

- Woody Guthrie: A Life

- Author

- Joe Klein

- Publisher

- New York: Delta, 1980

- ISBN

- 0-385-33385-4

Review Copyright © 2006 Garret Wilson — 27 May 2006 8:30am

This book blew my mind. What a story.

In music class in Middle School they taught us that Woody Guthrie had been born in Oklahoma. They told us that he was famous for writing songs, including “This Land is Your Land.”

But they didn’t tell us that Woody’s father, Charley Guthrie, had been a Ku Klux Klan member in Okemah, Woody’s home town (23), and that Charley had been part of a mob that lynched a nearby black family (10). They also didn’t tell us how Woody, as he grew older, became a champion for equal rights and integration at a time when even singing with other races was considered by many to be against the ways of society. In one gleeful episode, a host in New York wouldn’t let Woody eat at the same table as his African American friends, even though he had just sang with them; Woody responded by overturning the buffet table and quietly walking out (259).

They also didn’t tell us that Woody was a Communist. Well, not your normal, everyday Communist—Woody wasn’t your normal, everyday anything. At times you couldn’t tell whether Woody was hanging out with the Communists because he understood and espoused the intricacies of their philosophy, because he identified with their persecution from being on the fringes of American society, or because they provided him a concept of justice to pursue.

And they certainly didn’t tell us about Woody’s short life, which had more twists of fate (the old cruel brand of fate) than a fictional novel. His mother had Huntington’s disease—a hereditary sickness for which there is still no cure, in which the brain slowly degenerates leaving the person with little control over flailing limbs and robbing them of reason. When he was a child, Woody’s sister was burned to death. His father, Charley, was later badly burned in some strange episode with Woody’s mother and a kerosene lantern. Woody daughter later met her death in flames because of an electrical fire, and Woody himself had scary brush with fire that enveloped his right arm.

In Joe Klein’s book, Woody Guthrie: A Life, Woody comes across as simple, but never naïve; a real hobo (who would sometimes forsake bathing) who nevertheless seemed to know how to play up his “aw, shucks” kid from Oklahoma persona and quickly adjusted to New York life. His music was simple, but from a bird’s eye view as a whole his work was powerful. Perhaps genius.

From Woody’s increasingly stricken beginnings in Oklahoma, Woody the hobo struck out to California as did many Oklahomans during the Dust Bowl of the 1920s and 1930s. Woody just decided to sing about it. He sang the old country (not Country as in Country/Western, which was a genre that had not yet been invented) songs that he had heard his mother sing. He sang the songs of the poverty-stricken wanderers he met on the trains he caught. He sang the songs of the Okie workers in the orchards in California. And he made up plenty of his own.

Somewhere around World War II country music turned into its own genre: folk music. Somewhere around California and New York Woody became the center of it. He wrote tunes, and he wrote lyrics to tunes from other people’s songs and even to those of his own. He popularized, along with an African American named Leadbelly, an obscure form of Negro blues called “talking blues” (84), long before those same roots evolved into gangsta rap (470). And he wrote, scribbled, and notated. His creative mind was always turning. Take a small something that he wrote and it doesn’t look like much; look at everything he wrote and you know that something was up.

Woody’s life was soon up as well, as it was discovered that he had inherited Huntington’s disease from his mother. Soon Woody was wasting away at a mental hospital, but before it was all over the likes of Robert Zimmerman (better known as Bob Dylan) would gain their inspiration sitting at his feet and trying to walk in his footsteps. Woody was quite a character, but not a hero. Woody’s work was huge and diverse, but it was not an unbelievable achievement. His life was tragic, but not that unusual. Take them all together, though—Woody’s personality, his achievements, and the cruelty that fate answered to his unbridled creativity and social agenda—makes Klein’s depiction of Woody’s life one of the most amazing biography’s I’ve read.

Copyright © 2006 Garret Wilson